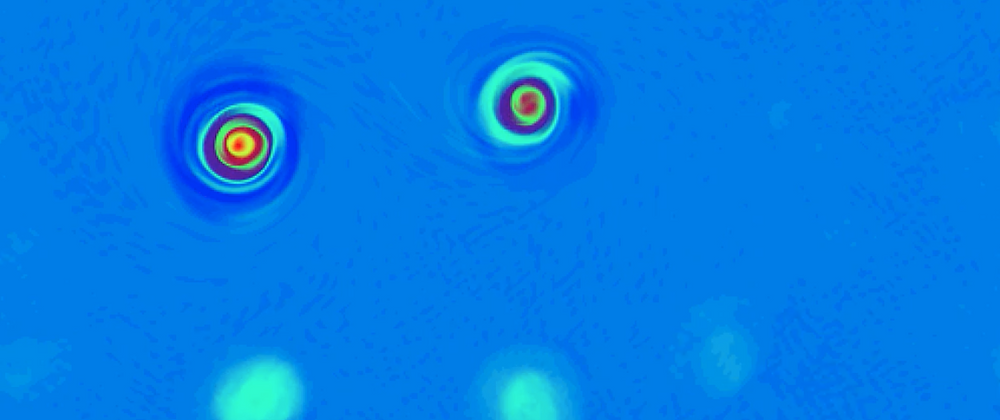

In this post I share my experience about how easy is it to add GPU-capable pieces of software to a fluid dynamics software in the Julia programming language with the help of CUDA.jl and Oceananigans.jl. All the code shown in this blog post can be found here

Oceananigans.jl is described as "A Julia software for fast, friendly, flexible, ocean-flavored fluid dynamics on CPUs and GPUs. It developed as a part of the Climate Modelling Alliance. It really delivers what it promises, as running one of the example simulations on GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) is just as easy as changing one line in a script to read "GPU" instead of "CPU".

One of my favorite things about the julia language is that the distance between a "user" and a "developer" is much smaller than in other high-level languages. This means that if you are able to write a script to run a simulation using another person's package, you have almost all the skills needed to write fast code that performs as well as writing code in the C language (the golden standard) and that looks similar to the implementation of most functions available in the language.

Here, I show how working with Oceananigans.jl is a fantastic experience, and that extending its capabilities to work on a GPU is almost as easy as doing it for CPU.

What I want to do is to extend the Shallow Water model in Oceananigans, and implement a representation of convection. If you are not interested in details of this model, you can skip the next section and go straight to the Implementation.

The model

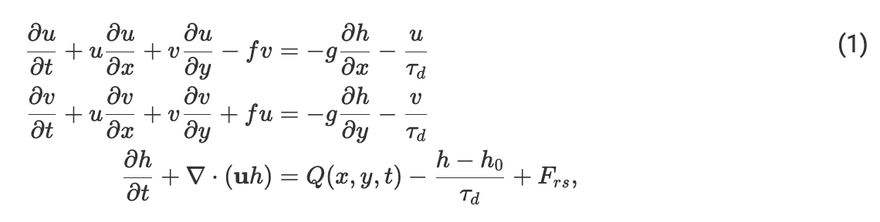

The model we are implementing is that in Yang 2013. The full set of equations that we will solve is:

These are the well-known shallow water equations that are already solved by the Shallow Water model in Oceananigans.jl. We added some damping in all the fields to be consistent with other studies, and a forcing to the height field. This is our convective parameterization that adds "mass" to the h field in the following way:

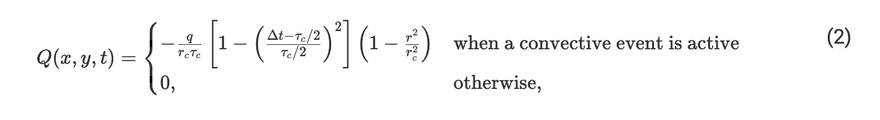

where q, t_c and r_c are the magnitude, radius and duration of convective events, Δt is the time that has passed since the convective event started and r is the distance from the point in which a convective event was triggered. Each convective event is triggered when the mass of the system exceeds certain threshold, representing a mass sink. This parameterization is interesting because it can reproduce some forms of organized convection like the Madden-Julian oscillation which affects the weather in a good portion of the globe and that continues to puzzle scientists. We want to use this to study how hurricanes form and intensify.

The implementation

Implementation attempt 1

Let's think about only one point in the grid. Our roadmap is:

- Check if this point (i,j) meets the conditions to inject mass.

- If it is convecting, go through its sorroundings, adding mass to each neighbohr.

Parallel programming requires to think things differently (or avoiding a race condition)

While the previous roadmap seems reasonable, it has a limitation: it cannot easily be paralellized. Imagine one point (A) that falls between two convective events (C1 and C2). The paralellization strategy would be that each different processing unit (could be each core of a CPU/GPU or each task) would take care of one convective event. When adding mass, each convective event will read the original value stored in A and add its own share of mass. This can happen in two ways:

- C1 reads the intial value of A and adds mass to it. C2 reads the updated value and adds mass to it. Success!

- C1 and C2 read the original value of A and they both add mass to it. Then they update with their own new value at the same time. Error! The final value does not contain the mass from both convective events, but only from the latest that wrote its updated value. This is called a race condition.

The problem will get worse if we have more than two convective events adding mass at the same time. We need to rethink the strategy.

Implementation attempt 2

If we expect to parallelize the problem, we need another strategy. Here is a second proposal.

Let's think again about one point (i,j) in the grid.

- Go through its sorroundings.

- If any neighbohring point is convecting, add mass to (i,j).

The difference is subtle, but if we paralellize the second proposal, no race condition exists, as each point in the "mass" array would only be written by one processing unit at each timestep. We will go with this one. This can be called an "embarassingly parallel" problem because each processing unit can do its own task without worrying about exchanging information with the others. This something GPUs are very good at and this feature motivates the rest of the work.

CPU implementation

To implement our convective parameterization, we will need two auxiliary arrays. One will store a boolean condition to indicate if each point is convecting. The other will store the time at which each point started convecting the last time. Lets called them isconvecting and convection_triggered_time. These two will have the same size as the h field and other fields in the domain. Now, we need a function that, at each time step, evaluates the conditions at each point of the domain and decides is the convective parameterization must act. Now we want that each time step, these two arrays are updated with current information about what points should be convecting.

For each point in the domain

Compute the time it has been convecting

Has this point been convecting less than intended? or

Is this point below the convective threshold? or

Is this point a new convecting point?

If any of these three conditions is true

update an array to indicate that this point is convecting and indicate when it started

end

end

Which in julia looks like this

function update_convective_events_cpu!(isconvecting,convection_triggered_time,h,t,τ_convec,h_threshold)

for ind in eachindex(h)

time_convecting = t - convection_triggered_time[ind]

needs_to_convect_by_time = isconvecting[ind] * (time_convecting < τ_convec) #has been convecting less than τ_c?

needs_to_convect_by_height = h[ind] >= h_threshold

will_start_convecting = needs_to_convect_by_height * iszero(needs_to_convect_by_time) #time needs be updated?

needs_to_convect = needs_to_convect_by_time | needs_to_convect_by_height

isconvecting[ind] = needs_to_convect

convection_triggered_time[ind] = ifelse(will_start_convecting, t, convection_triggered_time[ind])

end

return nothing

end

Now, we want each processing unit to add mass to only one point. How much mass? This depends on how many convecting points are around it, how far they are, and for how long each one has been convecting.

Something like:

For each neighbor

Is this neighbor convecting? then

How far is this?

For how long has it been convecting?

add_mass_to_myself(distance, time)

end

end

Which in julia looks something like this:

function heat_at_point(i,j,k,current_time,τc,isconvecting,convection_triggered_time,numelements_to_traverse, heating_stencil)

forcing = 0.0

nn = -numelements_to_traverse

np = numelements_to_traverse

for neigh_j in nn:np

jinner = j + neigh_j

for neigh_i in nn:np

iinner = i + neigh_i

if isconvecting[iinner , jinner]

forcing = forcing - heat(current_time,convection_triggered_time[iinner,jinner],τc,heating_stencil[neigh_i,neigh_j])

end

end

end

return forcing

end

GPU implementation

Now. This is where the magic happens. Something great about Oceananigans.jl is that is has most of the infraestructure ready to help you plug in some forcing to the model fields. This forcing can then be run on whatever architecture you have chosen (GPU or CPU). In this case our heat_at_point function is generic enough that Oceananigans.jl can work with it.

However, because Oceananigans.jl does not manage our isconvecting and convection_triggered_time arrays we need to write a function to update them using the GPU. Fortunately, CUDA.jl is another library that exposes most of the functionality of cuda (the set of tools to run general purpose code in a Nvidia GPUS) from julia. Doing just minimal changes, our new function looks like this:

function update_convective_events_gpu!(isconvecting,convection_triggered_time,h,t,τ_convec,h_threshold,Nx,Ny)

index_x = (blockIdx().x - 1) * blockDim().x + threadIdx().x

stride_x = gridDim().x * blockDim().x

index_y = (blockIdx().y - 1) * blockDim().y + threadIdx().y

stride_y = gridDim().y * blockDim().y

for i in index_x:stride_x:Nx

for j in index_y:stride_y:Ny

time_convecting = t - convection_triggered_time[i,j]

needs_to_convect_by_time = isconvecting[i,j] && (time_convecting < τ_convec)

needs_to_convect_by_height = h[i,j] >= h_threshold

will_start_convecting = needs_to_convect_by_height && iszero(needs_to_convect_by_time)

isconvecting[i,j] = needs_to_convect_by_time || needs_to_convect_by_height

will_start_convecting && (convection_triggered_time[i,j] = t)

end

end

return nothing

end

The only significant change that we did is in the way we iterate over the fields. In this case, each processing unit will be in charge of only a handful of operations so we don't need to make a loop over all of the element in the array. This kernel will be passed to each processing unit.

This gives a considerable speedup to run simulations like those shown in the beginning.

With julia and Oceananigans.jl, the code is so reusable and versatile, that you can devote more time to explore your simulations than to writing them. And you also enjoy the writing!

You can see the full implementation of the convective parameterization in here

Resources:

- Yang and Ingersoll (2013) Triggered convection, gravity waves, and the MJO: A shallow water model

- The julia language (https://www.julialang.org)

- Oceananigans.jl (https://github.com/CliMA/Oceananigans.jl)

- CUDA.jl (https://github.com/JuliaGPU/CUDA.jl)

Top comments (1)

Add to the discussion