Read the original article and subscribe to my blog on The Scientific Coder.

I love thinking visually by drawing doodles and schematics for my work. It's one of my favorite things to do, next to coding. When working with the Julia language, one visualization I enjoy is seeing the type space of a method that you are dispatching on. Normally I do this in my mind's eye, but let me clarify this by drawing some actual figures.

To start with the basics; Julia has functions and methods. A function is simply the name, like push! or read. Methods are specific definitions of a function, for certain types of arguments. Take for example push!(s::Set, x) or read(io::IO). From an object-oriented perspective you could say that methods are instances of functions.

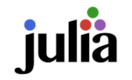

For any given method you can consider the dispatching as slicing a part of the entire possible type space of that given function. For a given set of arguments of course. If you increase the number of arguments in the function definition, then more dimensions get added to the type space. I don't even know how to find the best written words for this, the visualization above just feels intuitive to me.

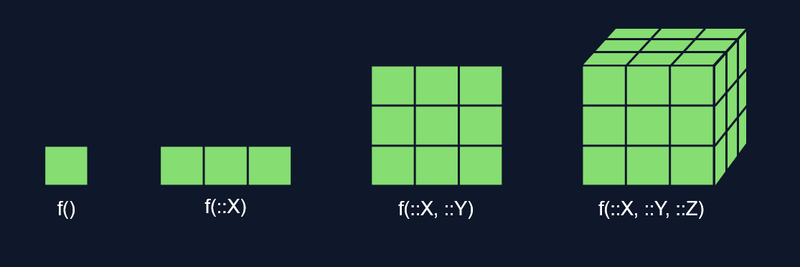

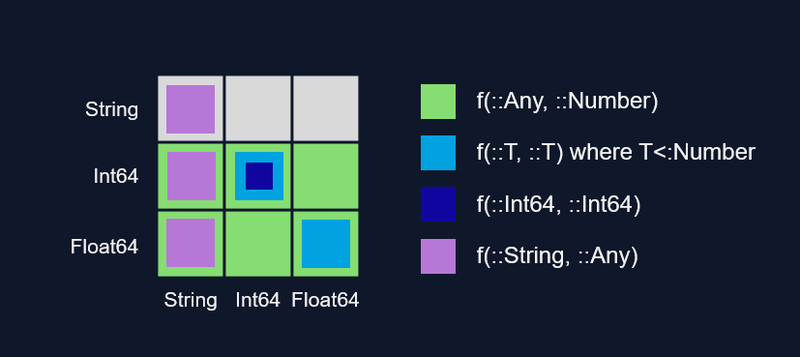

Let's take the function f and imagine for a moment that there are only 3 types in the whole Julia type universe: the Float64, Int64and the String. The Float64and the Int64are a subtype of Number, which is obvious I hope. By default in Julia if you specify no type in your function argument, then it will be assumed you mean the Anytype, of which every other type is a subtype.

A method f(::Any, ::Any) thus describes the entire space of all possible types for the function named f. On the other hand, a method like f(::Int64, ::String) is super concrete, it's a singular point in the type space.

You can use abstract types like Number or unions like Union{Float64, Int64} to capture a subset of the discrete type space. This way you can choose which part you want to define for your function, with the chosen set of types you will be dispatching on at runtime. Abstract types in Julia exist only for this dispatching purpose, to dispatch on a set of subtypes, they have no other influence on their subtypes what so ever. They are not dictators like classes in other languages.

I like these visuals. Some junior engineers wonder what "diagonal dispatch" is. I don't have any other way of explaining the concept then by just drawing it. The figure is immediately obvious. Diagonal dispatch happens when the type of all arguments is forced to be equal with f(::T, ::T) where T. This truly represent a diagonal through the type space. You can see it in the example above. You can also limit the diagonal dispatch to a subset with f(::T, ::T) where T<:Number and in higher dimensions you can be fancy like f(::T, ::T, ::S) where {T<:Number, S<:AbstractString} by adding multiple of these parametric types.

Note that when you define a method twice, you have to take care that it is clear which method gets dispatched on. The compiler will prioritize the one that is most concrete, so the one that is most specific about the types. In the figure above, I ordered them from most specific to least specific. You can try for yourself to see if I ordered them correctly.

For example if you define the following:

f(::Any, ::Any) = println("any & any")

f(::Int64, ::Int64) = println("int & int")

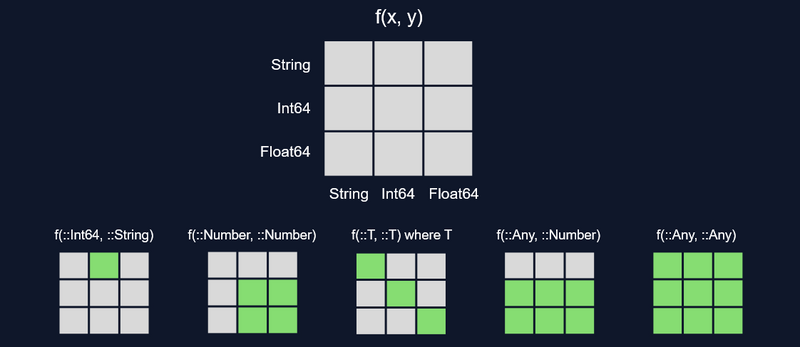

Then most function calls will run the broadest method because that one is defined for the whole type space, but when you input two integers you will call the very specific method f(::Int64, ::Int64). Let's give it a go:

julia> f("string", 5)

any & any

julia> f(4, 5)

int & int

From a visual perspective, we have created an overlapping dispatch, where one method is specifically defined for the integer case f(::Int64, ::Int64) and will be called when only integers are used as arguments.

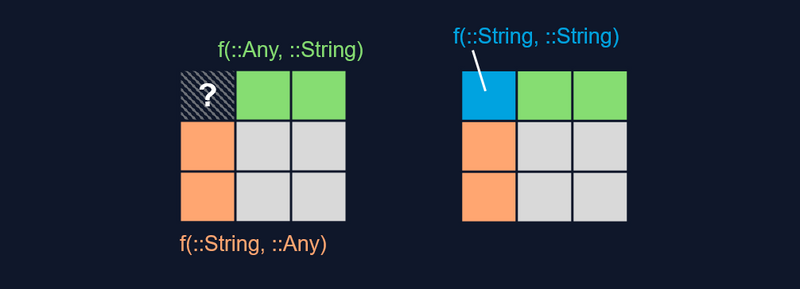

There are some caveats here. If you are not careful the methods can become ambiguous and Julia won't like that. For example if you define the following:

f(::Any, ::String) = println("any & string")

f(::String, ::Any) = println("string & any")

Which one of these methods should be called with f("string", "string")?

julia> f("string", 5)

string & any

julia> f(5, "string")

any & string

julia> f("string", "string")

ERROR: MethodError: f(::String, ::String) is ambiguous. Candidates:

f(::Any, ::String) in Main at REPL[8]:1

f(::String, ::Any) in Main at REPL[9]:1

Possible fix, define

f(::String, ::String)

Yikes, that's impossible! Fortunately there is a fix proposed, by explicitly defining the ambiguous case. Though perhaps you should reconsider what your actual intentions are in this design. The visual representation below hopefully makes the mistake more clear. At first there is confusion because the two dispatches overlap and neither is more specific than the other, but we can fix it by defining a more concrete method in the conflicting area.

When you define a lot of methods, you are creating a colorful patchwork in the type space of your function. You can come up with the craziest designs in your methods, but be careful. Finding the right balance of a few big broad abstract methods versus multiple tiny concrete methods is a true art in Julia.

People do not often share how they visualize the code design in their mind, while I believe this really shapes the creative process. The closest visual representation in Julia I have seen is the article about Julia's dispatch with Pokemon types. You can read that for more detailed examples with Julia's multiple dispatch.

That concludes this short artsy post, but I hope it helps the visual thinkers in the programming community! Let me know if you use different kinds of visualizations in your coding work. And don't forget to subscribe to my newsletter.

Top comments (0)